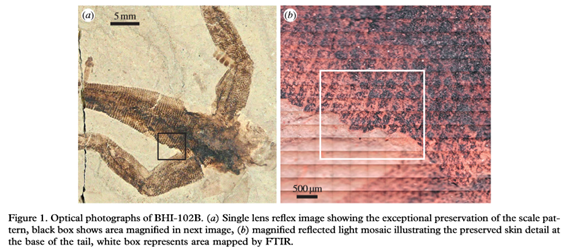

Optical photographs illustrate amazingly preserved skin detail of dinosaur tissue. The detail of ancient accounts of dragons render specific details regarding scales, textures, spikes, color, and other armor specifics these “terrible lizards” possessed.

It raises a question: how did these ancient societies know such details about dinosaurs many hundreds of years before paleontology was even invented? Could it be that these details were so well known (accounts found on every continent on earth) because mankind walked with such dragons (dinosaurs) and pterodactyls?

https://www.genesispark.com/exhibits/evidence/historical/dragons/

Marco Polo wrote on huge serpents, he described as having “two short legs” with “three claws on each leg”. He noted they “dwelled in caves during the day to avoid the heat”. The serpents had “jaws wide enough to swallow a man, teeth large and sharp, and their whole appearance is so formidable that neither man, nor any kind of animal can approach them without terror.”

Polo, Marco, The Travels of Marco Polo, 1961, pp. 158-159.

Herodotus wrote: “There is a place in Arabia, situated very near the city of Buto, to which I went, on hearing of some winged serpents; and when I arrived there, I saw bones and spines of serpents, in such quantities as it would be impossible to describe. The form of the serpent is like that of the water-snake; but he has wings without feathers, and as like as possible to the wings of a bat.”

Herodotus, Historiae, tr. Henry Clay, 1850, pp. 75-76.

Egyptian representation of tail vanes with flying reptiles and concluded that they must have observed pterosaurs or they would not have known to sketch this leaf-shaped tail.

Goertzen, J.C., “Shadows of Rhamphorhynchoid Pterosaurs in Ancient Egypt and Nubia,” Cryptozoology, Vol 13, 1998.

During the Medieval period, the Scandinavians described swimming dragons. The Vikings placed dragons on the front of their ships to scare off such “sea monsters”. The oldest reliable sea serpent record we have was written by Olaus Magnus in his book Historia de Gentibus. The story describes a Catholic priest who was exiled from his Swedish homeland and saw a sea monster “of an astonishing size” (about 75 ft long). This sea monster was sighted in 1522 near an island named Moo. Magnus’s credibility is attested by his most famous work, the 1539 book Carta Marina, which presented the most accurate map of Scandinavia or any other European region in existence at the time.